Although it has dominated recent headlines, Eastern equine encephalitis virus (known as EEE or triple E) is actually not new. It is only one of multiple mosquito-borne encephalitis viruses, along with the well-known West Nile virus. Historically, severe neuroinvasive EEE infections are generally uncommon. From 2009 through 2018, an average of only 7 cases were reported annually. In 2019, however, reports of severe encephalitis (swelling and dysfunction of the brain) and death have been reported in 22 U.S. states, mostly around the Atlantic and Gulf coast, and in the Great Lakes region. Unfortunately, EEE virus is untreatable and is the most severe of the arboviral encephalitides with a mortality of at least 30 percent. Many who do recover from the illness are still left with permanent neurological problems.

<a name=\'more\'></a>

EEE is associated with a cycle of infection between the mosquito, Culiseta melanura, and wild birds that inhabit swampy areas along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the U.S. Because C. melanura rarely bite humans and humans generally do not inhabit swampy areas, EEE is very rarely transmitted to humans. However, Eastern equine encephalitis is occasionally picked up by other mosquito species (i.e. Aedes, Coquillettidia, and Culex) that feed on both humans and mammals, and are thus able to transmit the infection as well.

Although infections can occur throughout the year, peak incidence is in late summer through fall. Once infected with EEE, it typically takes four to 10 days before symptoms develop, which include fever, chills, fatigue and joint and muscle pain. EEE lasts anywhere from one to two weeks, and usually presents in two ways – either a generalized infection, known as systemic infection; or an infection centered in the brain and nervous system, known as neuroencephalitis. Children under the age of 15 and adults over the age of 50 are most likely to develop Eastern equine encephalitis, at six percent of infected children and two percent of infected adults.

In infants, the encephalitic form is characterized by the abrupt onset of central nervous system involvement. Older children and adults who develop encephalitis typically experience a first phase (prodromal phase) that mimics systemic infection, and then go on to develop signs and symptoms of nervous system involvement as well such as headache, irritability, restlessness, drowsiness, convulsions and coma. Gastrointestinal symptoms such as anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea and cyanosis are also common. Once neurologic symptoms begin, the clinical condition deteriorates rapidly, with approximately 90 percent of patients infected becoming comatose or stuporous. Seizures and focal neurologic signs including cranial nerve palsies develop in approximately half of patients infected, and, unfortunately, approximately a third of all people infected with Eastern equine encephalitis die from the disease.

Although inactivated vaccines are available for horses, there is no commercially available vaccine for humans. To protect against EEE, the only course of action is to avoid being bitten by a mosquito. This can be accomplished through the proper application of insect repellant that contains at least 20 percent DEET, picaridin or oil of lemon eucalyptus. It’s also important to wear closed-toe shoes, long pants and long-sleeved shirts when spending time outdoors, and to avoid wearing dark colors, floral prints and sweet-smelling perfumes and colognes while outside. If you are bitten by a mosquito and experience an adverse reaction or flu-like symptoms, see your health care provider immediately.

In addition to personal protection, eliminating mosquito breeding grounds is equally important. If you have a mosquito problem on your property, be sure to empty areas of standing water and contact a licensed pest control professional to help assess the situation and develop a mosquito management plan specifically for your property.

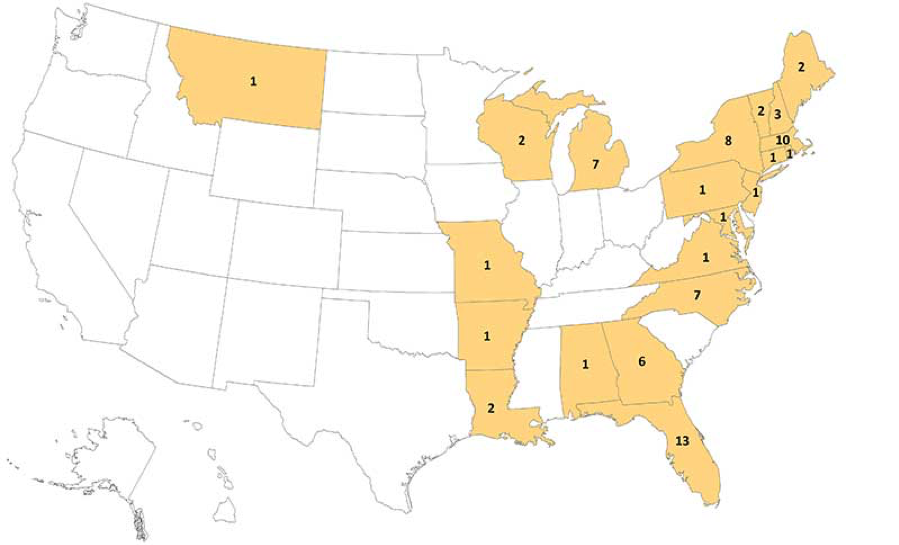

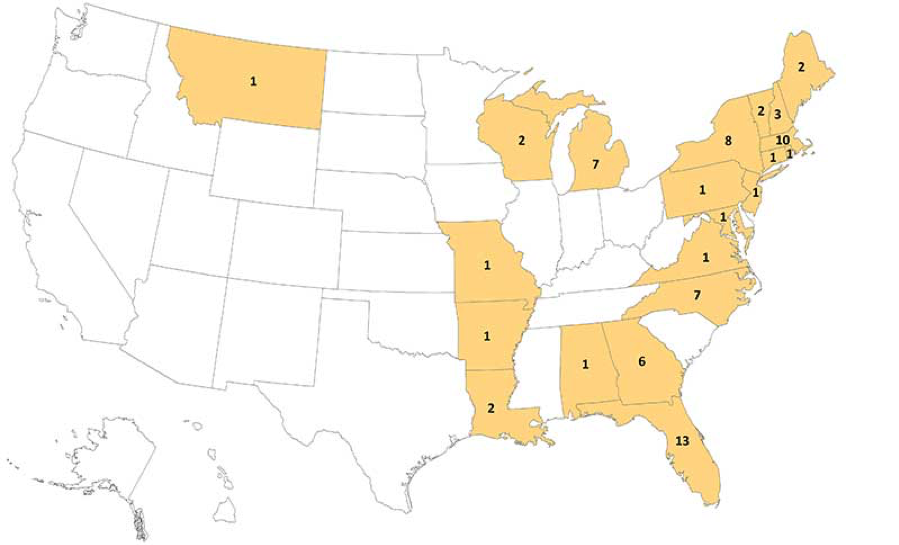

Neuroinvasive cases of Eastern Equine Encephalitis 2009-2018

https://archive.janatna.com/

Neuroinvasive cases of Eastern Equine Encephalitis 2009-2018https://archive.janatna.com/

Neuroinvasive cases of Eastern Equine Encephalitis 2009-2018https://archive.janatna.com/